The Yogyakarta Sultanate is a Javanese monarchy established in 1755 following the Treaty of Giyanti. This treaty led to a split of the powerful Mataram Sultanate into Yogyakarta and Surakarta. Sultan Hamengkubuwono I found the Yogyakarta Sultanate, making it as a political, cultural, and spiritual center in Central Java.

Unlike many traditional monarchies in Nusantara that faded with colonialism and modern statehood, Yogyakarta adapted and played a critical role during Indonesia’s National Revolution. Due to it’s important role, Yogyakarta continues to hold a special autonomous status within the Republic of Indonesia.

In modern Indonesia, the Sultanate is not only a symbol of traditionalism and Javanese heritage. The sultanate became a unique case where monarchy and republic coexist.

Origins of Yogyakarta Sultanate

The Yogyakarta Sultanate traces its origins to the once-powerful Mataram Sultanate, an Islamic kingdom that rose to power in Java during the late 16th century. Over time, internal political conflicts and Dutch intervention weakened the Mataram Sultanate.

The decline culminated in the signing of the infamous Treaty of GIyanti on February 13, 1755. The Treaty officially split the Mataram Sultanate into two separate kingdoms:

- Surakarta Sultanate, under Pakubuwono III

- Yogyakarta Sultanate, under Prince Mangkubumi, who would become Sultan Hamengkubuwono I

With this treaty, the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) successfully divide many local power in Java and solidify its control over Java. By playing rival Javanese factions against each other, the Dutch gained greater influence in the region.

Originally, Prince Mangkubumi had been a key member of the royal family of Mataram. He showed discontent with the VOC’s interference in Mataram’s royal court. His dissatisfaction led to a rebellion and civil war against his brother Pakubuwono II and the Dutch.

Founding of Yogyakarta

The civil war laster for several years and caused deep political fractures in Java. In 1749, the resistance against the Dutch and Mataram court intensified, putting the Dutch control in contention. In response, the Dutch proposed a treaty that granted Prince Mangkabumi control of the southern half of Mataram.

There, Prince Mangkabuni established his new court in Yogyakarta, laying the foundation for a new Javanese kingdom. After the treaty, he changed his title as Sultan Hamengkubuwono I, where his dynasty continues to this day.

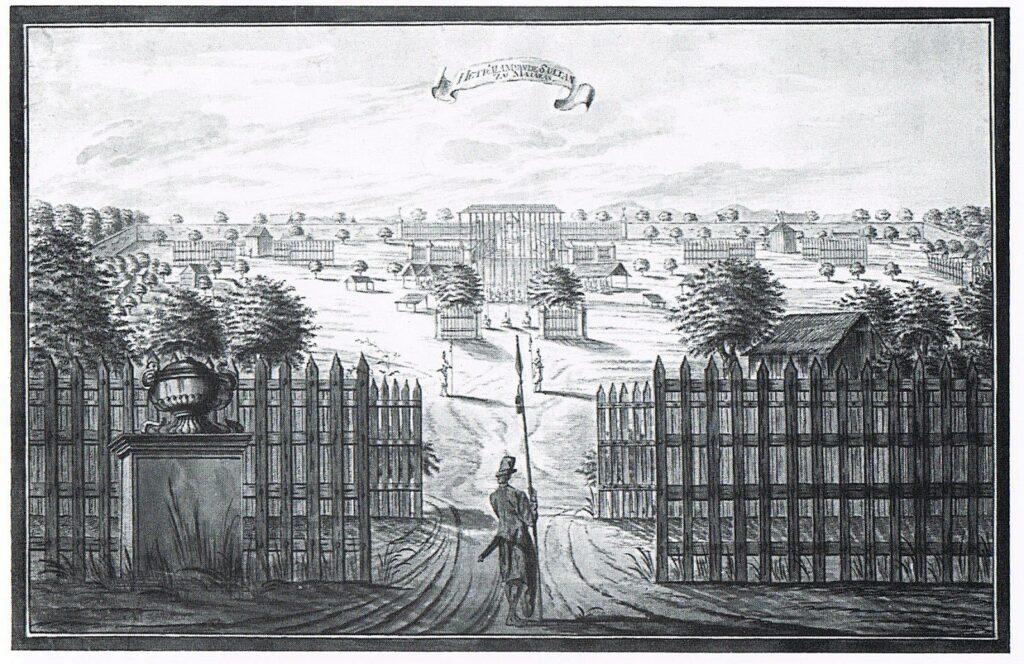

In 1756, he built his palace which widely known as the Kraton of Yogyakarta. This city and the royal palace became the heart of the new kingdom. The city of Ngayogyakarta Hadiningrat or Yogyakarta, grew rapidly around the kraton, becoming a new center of Javanese culture, resistance, and islamic monarchy.

Yogyakarta During The Colonial Period

Although the newly-formed Sultanate under Sultan Hamengkubuwono I retained their autonomy, the dutch under VOC heavily influenced the sultanate’s political decisions. As a result, VOC expanded its presence in Java, with Dutch residents stationed at the Kraton (Royal Palace) to serve as advisors that dictated key political, military, and economic decisions.

When the VOC collapsed in 1799 due to corruption and bankruptcy, the Dutch colonial state took over all their holdings in Nusantara. The new Dutch rulers pursued firmer control of the Yogyakarta sultanate, seeking to convert symbolic influence into direct governance.

However, Dutch control did not last long, especially when the British defeated the Dutch in Java back in 1811. During this year, The British Colonial chose Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles as Lieutenant-Governor of the island.

In response, Sultan Hamengkubuwono II started a resistance toward the British and soon clashed with Raffles. Frustrated with the Sultan’s continuous opposition, Sir Stamford Raffles authorized a military assault on Yogyakarta, deploying a force of 1,000 troops composed of grenadiers, royal artillery, dragoons, and Indian sepoys.

In June 1812, British troops under Colonel Gillepsi stormed the Kraton of Yogyakarta in a surprise offensive. In less than 1 night, the British troops controlled and looted the Kraton, marking the first time a European military force had physically invaded a Javanese royal court. The consequences were humiliating for the sultanate:

- Sultan Hamengkubuwono II was forced to abdicate once again.

- The British installed his son, Hamengkubuwono III as a puppet ruler.

- The British brought royal treasures and artifacts to Britain.

The return of the Dutch to Yogyakarta

The British reinstated the Dutch colonial rule in 1816, it returned stronger and more centralized. The Dutch learned from both VOC’s failure and the British administration in managing their colonies. The Dutch began restructuring its control over the Javanese royal territories.

Yogyakarta along with Surakarta, became the Dutch’s Vorstenlanden, which widely known as semi-autonomous princely states under direct colonial supervision. This system allows Sultan to have full control over religious and cultural matters. Meanwhile, the Dutch colonial had control on governance, foreign relations, taxations, military, and land policies.

Although the sultanate remained, it has no more political authority and seen by many as a puppet government. Nevertheless, this period saw cultural resurgence in Java:

- The royal court continued to preserve traditional arts, literature, and ceremonies.

- The city of Yogyakarta became a cultural stronghold for Javanese culture and identity in an increasingly Western-dominated rule.

Yogyakarta Sultanate role in the Java War

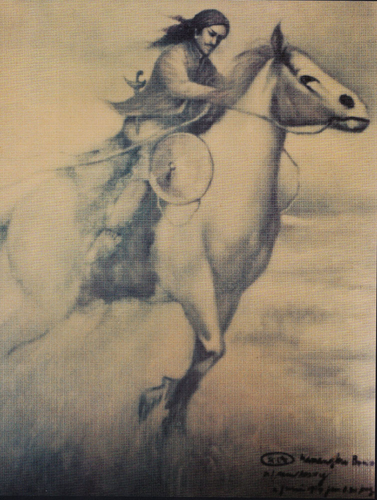

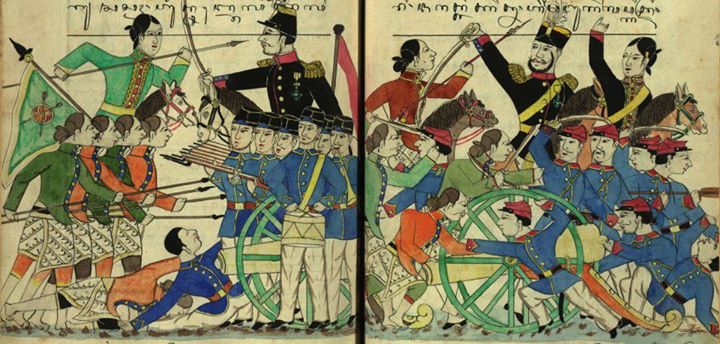

Yogyakarta Sultanate’s colonial era experience marked by strong internal resilience in a face of subjugation. From 1825-1830, the famous Prince Diponegoro, the eldest son of Hamengkubuwono III and the heir to the throne of Yogyakarta lead a famous resistance against the Dutch. This resistance erupted and became a full-scale war known as the Java war.

Diponegoro’s forces used a guerilla warfare framed the war as jihad (holy struggle) against foreign invaders. Over the five-year conflict, both parties suffered heavy casualties with 200,000 Javanese died and 15,000 Dutch soldiers, making it one of the deadliest wars in Indonesia’s colonial history.

After the war, the war weakened the sultanate’s power even more and made the Dutch to consolidate colonial power more aggresively. However, the Sultanate still maintained its cultural leadership and laid a solid groundwork for its later role in the Indonesian independence movement.

In addition, the war drained the Dutch finances and exposed the risks of direct confrontation with local kingdoms. In response, the Dutch implemented Cultivation System or cultuurstelsel (1830s onward), a forced-labor policy aimed at generating revenue from cash crops like sugar and coffee.

For Indonesia, the war became Indonesia’s most enduring symbols of anti-colonial resistance. Diponegoro himself emerged as a legendary figure in the national consciousness. His resistance against the Dutch turned him into a symbol of patriotism and sacrifice. In recognition of his contributions, the Indonesian government honored him as a National Hero of Indonesia, where his legacy still continues to inspire the younger generations.

The Sultanate’s Role during Indonesian National Revolution

Between 1900 and 1945, the Sultanate of Yogyakarta navigated a complex period of colonial rule, administrative reform, and wartime occupation. During this period, the Sultanate retained nominal autonomy as self-governing native state, still with limited political freedom.

Sultan Hamengkubuwono VII, maintained diplomatic relations with the colonial administration, promoted modernization in education and infrastructure. His successor, Sultan Hamengkubuwono VIII, continued his father’s policies in balancing traditional authority with gradual reform.

By the early 20th century, the archipelago witnessed growing nationalist sentiments, where the sultanate’s intellectuals began engaging with ideas of independence from the colonial rule. However, situation changed drastically during the occupation of Japanese forces in the Dutch East Indies.

The Japanese allowed the Yogyakarta Sultanate to function with relative autonomy under close surveillance. Sultan Hamengkubuwo IX ascended to the throne in 1940, used this period to build administrative experience and protect his people from forced labor and food shortages.

By the end of the Second World War, there was a political vacuum across the archipelago, including Java. With political chaos in the region, the Sultan emerged as a stabilizing force in Central Java. Under the leader of Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX, the sultanate support the idea of a sovereign Indonesian republic.

The Sultanate’s Role in Supporting the New Republic

After Indonesia’s declaration of independence, the Dutch returned and tried to maintain their power in Indonesia. The sultanate of Yogyakarta played a crucial role in supporting Indonesia’s effort to keep its independence (Wiszowaty and Wahyuni, 2023).

After less than a month after Indonesia’s independence declaration, Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX issued an announcement that Yogyakarta will be the part of the new republic. In addition, During the Dutch occupation of Batavia (Modern-Day Jakarta), the city of Yogyakarta became the temporal capital of Indonesia from 1946-1949).

The 5th September announcement became a key that shaped a mixed political system of monarchy inside the Republic of Indonesia. During that time, Yogyakarta met the conditions to become a separate state, where the sultanate has it owns territory, population, resources, government, and stable foreign relations.

Instead of establishing a separate statehood, the Sultan declared Yogyakarta part of the new republic. The Sultan’s action perceived as a special form of recognition of Indonesia, which strengthened its position as a new state.

After the Dutch formally transferred sovereignty in December 1949, Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX officially dissolved his sovereign rule and allowed Yogyakarta to fully integrate into the republic. In 1950, the central government granted Yogyakarta an autonomy status, where it became Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta (Special Region of Yogyakarta), with the Sultan serving as Governor for life—a unique arrangement that still exists today.

Yogyakarta Sultanate’s in Modern-Day Indonesia

In today’s modern-day Indonesia, Yogyakarta Sultanate holds a unique and influential position. While most sultanates in Indonesia serve only symbolic and cultural roles, Indonesia gave Yogyakarta an exception, where its Sultan serves as a governor.

In recognition of Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX’s loyalty, the Indonesia government granted Yogyakarta special administrative status through Law No. 13/2012, officially designating it as he Special Region of Yogyakarta (Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta or DIY).

Today, the reigning monarch, Sultan Hamengkubuwono X, not only continues the cultural traditions of the Sultanate, but also serves as the governor of Yogyakarta. This role passed by royal lineage rather than election. His leadership combines traditional Javanese monarchy with modern regional governance, making Yogyakarta a living model of cultural preservation coexisting with republican ideals.

Moreover, the Sultanate of Yogyakarta continues to play a key role in safeguarding Javanese culture, heritage, and language. The royal palace (Kraton) remains a center of traditional arts, court rituals, and spiritual authority, attracting both scholars and tourists from around the world.

References

https://www.kratonjogja.id/cikal-bakal/

Sejarah Kesultanan Surakarta dan Yogyakarta dalam Perjanjian Giyanti

https://dioramaarsip.jogjaprov.go.id/sejarah?periode=2

Wiszowaty, M.M. and Wahyuni, I., 2023. Monarchy in the Republic – Sultanate of Yogyakarta in the Republic of Indonesia. Przegląd Prawa Konstytucyjnego, (6), pp.321–336. Available at: https://doi.org/10.15804/ppk.2023.06.23 [Accessed 8 June 2025].