Indonesia with its national motto of Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (Unity in Diversity), strives to ensure equal treatment for all ethnicities across their archipelago. The commitment is particularly significant in the case of minority groups, including the Chinese-Indonesian community.

Over the centuries, Chinese-Indonesians have become an integral part of the nation’s social, cultural, and economic fabric, which contributes to Indonesia’s diversity and richness in history. Today we will explore the history of Chinese people in Indonesia.

Chinese Indonesian, Who are they?

The Chinese Indonesians or simply known as orang Tionghoa, are Indonesians whose ancestors arrived from China at some stages in the last eight centuries. Chinese Indonesians considered to be the fourth largest community of Overseas Chinese after Thailand, Malaysia, and the United States. Most of Chinese Indonesians came from either Fujian or Guangdong province in Southern China. With dominant languages of Hokkien, Hakka, and Cantonese.

Regarding their number, population of Chinese Indonesian remains a topic of debate, particularly due to the lack of official census data in the past. Some scholars estimated that the Chinese community numbers around 6 million people, or 3% of Indonesia’s population. While other suggest it could be as high as 10 million, or 5% of the total population.

Early Chinese Migration to the Indonesian archipelago

The Chinese came to Nusantara for the first time in the 7th century during the Tang dynasty. However, the most notable waves of migration happened during the Song dynasty (10th-13th century), Yuan dynasty (13th-14th century), and Ming dynasty (14th-17th century).

Chinese traders, primarily from Fujian and Guangdong traveled to Indonesia seeking valuable commodities such as spices, sandalwood, and gold. In return, the Chinese brought silk, ceramics, and other goods from China. Ports like Sunda Kelapa (Jakarta) and Palembang made Indonesia an attractive trading hub for the Chinese. As trade flourished, many Chinese traders and sailors chose to settle in Indonesia. Some of them married the local women, leading to the emergence of a Peranakan Chinese.

One of the most famous migrations occurred between 1405 and 1433, where Zheng He led series of naval expeditions across Southeast Asia. His massive fleet established diplomatic ties and reinforced Chinese presence in the region. Some of his crew members decided to settle permanently in Indonesia.

Chinese Indonesian communities during Dutch Colonial Period

The Chinese became residents of java, Maluku, Kalimantan, Sumatra, and Sulawesi before the arrival of the Dutch. Like their predecessors, they settled in Indonesia for trading purposes. Many local regents appointed Chinese merchants as an intermediary traders between themselves, the local population, and external markets. These regents preferred the Chinese rather than the local, in order to prevent the rise of local merchant class that could challenge the regent’s position.

When the Dutch arrived, the Chinese Indonesian community played a significant and complex role in social and economic sector. The Dutch through the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the colonial administration, implemented policies that shaped the status of the Chinese community. These policies however, considered to be both beneficial and restrictive.

Social Segregation and Ethnic Classification

During the colonial period, the Dutch chose local headmen to be a leader of each ethnicities. The Dutch classified all Chinese from different speech groups (Hokkien, Hakka, Cantonese) as Chinese. The headman of the Chinese community widely know as Kapitan Cina or Chinese Captain.

In 1854, the Dutch colonial government divided the population of Indonesia into three groups. The European filled the first group, followed with Chinese, Arabs, Indians, and Japanese in the second group. Meanwhile, the local indigenous filled the bottom group, where the Dutch considered them as inferior.

Chinese Indonesians were classified as foreign orientals, which placed them above the local population. This status granted them certain privileges in trade, but also subjected them to strict regulation:

- Passenstelsel (pass system): required all Chinese people to carry special passes for travel outside designated areas.

- Residential restriction: forced in segregated districts known as “Chinatowns” (Pecinan), especially after the 1740 Chinese massacre in Batavia.

Economic Dominance and Social Stratification

Under the Dutch rule, the Chinese business people became indispensable to the colonial economy. The Dutch granted the Chinese to sell opium, operating gambling establishments, pawnshops, and many more. The Chinese also established themselves in industries like trade, finance, and agriculture (Chong, 2016).

Following the local regents, the Dutch often relied on Chinese Indonesians to be the middlemen in facilitating trade, collect taxes, and manage plantations. Also during this period, many Chinese involved in sugar production, retail trade, and tax farming.

The Dutch also implemented “divide and conquer” law to prevent the Chinese and indigenous population to combine forces, by separating their living area. This law automatically lead to minimum interaction between the two ethnicities. In addition, the Chinese began to occupy uncertain positions during the Dutch rule.

On the one hand, the Chinese played a crucial role in shaping the economy of Indonesia. On the other hand, the indigenous population perceived the Chinese as an outsiders, leading to growing suspicion and prejudice from the local.

Towards the End of the Dutch Rule

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Chinese Indonesian began advocating for their rights. Some aligned with the growing Indonesian nationalist movement, while others supported Sun Yat-Sen’s revolution movement in mainland China (Chong, 2016).

It should be noted that the political orientation of the Chinese was not the same. The Chung Hwa Hui (CHH) represented pro-Dutch Chinese community, while Indonesian Chinese Party (PTI – Partai Tionghoa Bersatu) represented pro-Indonesian Chinese. However, PTI not considered as a strong party since the wealthy Chinese businessmen were mostly pro-Dutch. Additionally, the Indonesian nationalist movement did not consider PTI as an Indonesian party.

During the end of the colonial rule, the Dutch allowed the Chinese to establish Chinese-language newspapers, Chinese-medium schools, and other Chinese organizations. The establishment of these organizations aims to keep the Chinese as a distinct ethnic group and prevent the Chinese to unite with the indigenous population.

Due to their exclusivity, many indigenous population doubted the loyalty of the Chinese. Before the independence, the locals suspected all Chinese in East Indies of allying with Dutch and China. Such stereotypes caused anti-Chinese violence in the early years of Indonesian National Revolution, especially during the infamous bersiap era that happened in 1945-1946.

Chinese Indonesian struggles in the 20th century

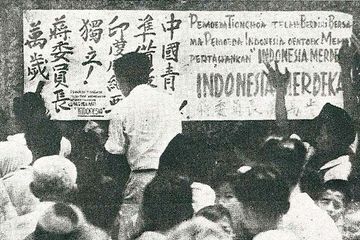

Chinese during Indonesian war of independence [1945-1949]

The Chinese-Indonesians found itself in a difficult position during the war against the Dutch. While some supported the independence movement, many remained neutral due to their historical ties with the Dutch colonial government. The neutrality of Chinese-Indonesians often misunderstood as siding with the Dutch. Additionally, many Chinese-owned businesses were often looted during this phase.

Despite their neutrality, many Chinese joined the fight against the colonial power along with their indigenous comrades (Subekti, 2023). Some of them became recognized as Indonesian national heroes:

- Admiral John Lie (1911-1988): A Chinese Indonesian naval officer, played a crucial role in smuggling weapons and medicines to support Indonesian independence movement. During this period, he used boats to bypass the Dutch navy and bring essential aid in Sumatra and Java. In 2009, his bravery earned him the title of pahlawan nasional (national hero).

- Yap Tjwan Bing (1910-1988): an important political figure who fought for Indonesian independence through diplomacy. As a member of a parliament after the independence, he worked to unify different ethnic groups in the archipelago, under the nationalist cause. He also played a role in drafting Indonesia’s first constitution.

- Siaw Giok Tjhan (1914-1981): Another key leader of Indonesian nationalist movement and an advocate for Chinese rights. He fought the Dutch neocolonial efforts and later became a minister under Soekarno’s government. He actively promoted the integration of Chinese Indonesians into Indonesia’s national identity. However, due to his ties with the Communist Party, he was imprisoned by Suharto during the New Order era.

Additionally, many Chinese Indonesians joined nationalist groups like Pemuda Republik Indonesia and Barisan Tionghoa Indonesia to support the independence movement. Some provided financial aid, medical supplies and weapons to the Indonesian fighters. Chinese-owned printing presses and newspapers like Sin Po, also helped to spread nationalist propaganda and rally support for independence.

Soekarno’s Orde Lama (Old Order)[1949-1965]

After Indonesia’s independence, many indigenous leaders viewed the Chinese as being more loyal to China than Indonesia. Their concerns stemmed primarily from the Chinese Communist Party’s victory in 1949, which led to concerns that the Chinese minority could act as a “fifth column” or an agent for China.

Another issue of dual citizenship also fuel further suspicion, as the 1946 and 1949 agreement allowed many Chinese Indonesians to hold both Chinese and Indonesian citizenship. Only in 1958, the government created citizenship law that required ethnic Chinese to formally renounce their Chinese nationality to retain Indonesian citizenship.

In the next year of 1959, Soekarno created a presidential decree to reduce economic influence of ethnic Chinese, where he banned Chinese from trading in rural areas. This forced many Chinese community to relocate from villages to urban centers. Additionally, the Indonesian government repatriated 119,000 Chinese citizens back to mainland China.

Despite citizenship and economic restrictions, the Order Lama government allowed Chinese Indonesians to maintain cultural and political representation. During this era, the government allowed the Chinese community to form ethnic organizations, operate Chinese-language media, schools and participation in politic.

Even during 1955 elections, the government reserved nine parliamentary seats for ethnic Chinese, and some Chinese politicians held cabinet positions. The government allowed the Chinese to keep their ethnic identity due to Soekarno’s close relation to China. Hence, he was relatively tolerant toward the Chinese-Indonesians.

Suharto’s Order Baru (New Order) [1965-1998]

During Suharto’s rise to power, anti-communist violence took on a strong anti-Chinese sentiment. Especially after the coup in 1965, thousands of ethnic Chinese accused as communist members were killed. After the massive revolution, Suharto’s regime enforced strict assimilation policies by banning Chinese cultural expressions like public celebrations, closing Chinese-language schools, banning Chinese medias and forcing changes in Chinese names.

Additionally, ethnic Chinese faced systematic discrimination, including different identity card known as SBKRI (Surat Bukti Kewarganegaraan) that marked them as different. This law disallowed ethnic Chinese to participate in politic, military, public service, state universities and also some economic restrictions.

Despite these restrictions, Chinese-Indonesians were largely confined to economic activities, which led to a perception of monopoly. During this period, some Chinese business tycoons developed closed ties with Suharto and his government, where the new order government benefited from these deals.

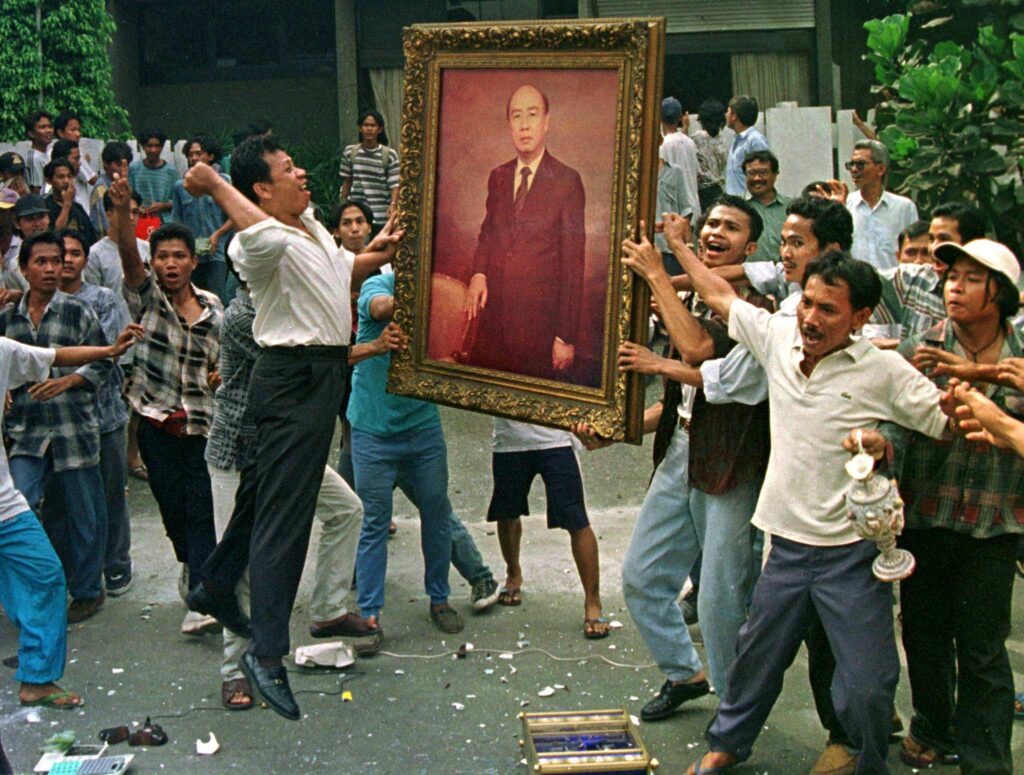

With Chinese-Indonesians primarily engaged in economic activities, the wealth gap between them and the indigenous population widened. The economic disparity fueled resentment, leading to another anti-Chinese riots like 1974 Malari riots and the 1994 Medan worker’s strike, where people looted Chinese businesses.

The worst outbreak of anti-Chinese riots occurred in 1998 amid the Asian Financial Crisis. This period is regarded as a dark chapter in the history of both Indonesia and its Chinese community, where rioters destroyed many Chinese-owned businesses and raped hundreds of Chinese women.

This wave of anti-Chinese sentiment contributed to the fall of Suharto’s new order. After Suharto’s resignation, Indonesia began to restore cultural and political rights of Chinese-Indonesians. Although discrimination toward the Chinese has reduced much in modern Indonesia, historical tensions from Suharto’s era continue to shape the Chinese-Indonesians today.

Chinese-Indonesian in Modern Indonesia

After the fall of Suharto in 1998, Indonesia underwent a new phase of democratization, leading to institutional reforms and a decline in anti-Chinese violence. Alleged mass rapes and military involvement during the riot gained sympathy from political elites and local leaders for the Chinese minority. In addition, cooperation of some Chinese tycoons in corruption investigation also eased further resentment.

Post-Suharto governments also removed discriminatory policies, which includes force assimilation. Former President Abdurrahman Wahid lifted restrictions on Chinese-language media, and Megawati Soekarnoputri declared Lunar New Year as a national holiday. In 2006, former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono passed a citizenship law ending distinction between indigenous and non-indigenous, granting Chinese-Indonesians equal rights that allow Chinese minority access to government positions.

With a new reformation, Chinese-Indonesians established social and cultural organizations and actively participated in politics. These reforms have also allowed Chinese-Indonesians to integrate more fully into Indonesian society while contributing in politic, economic, and culture.

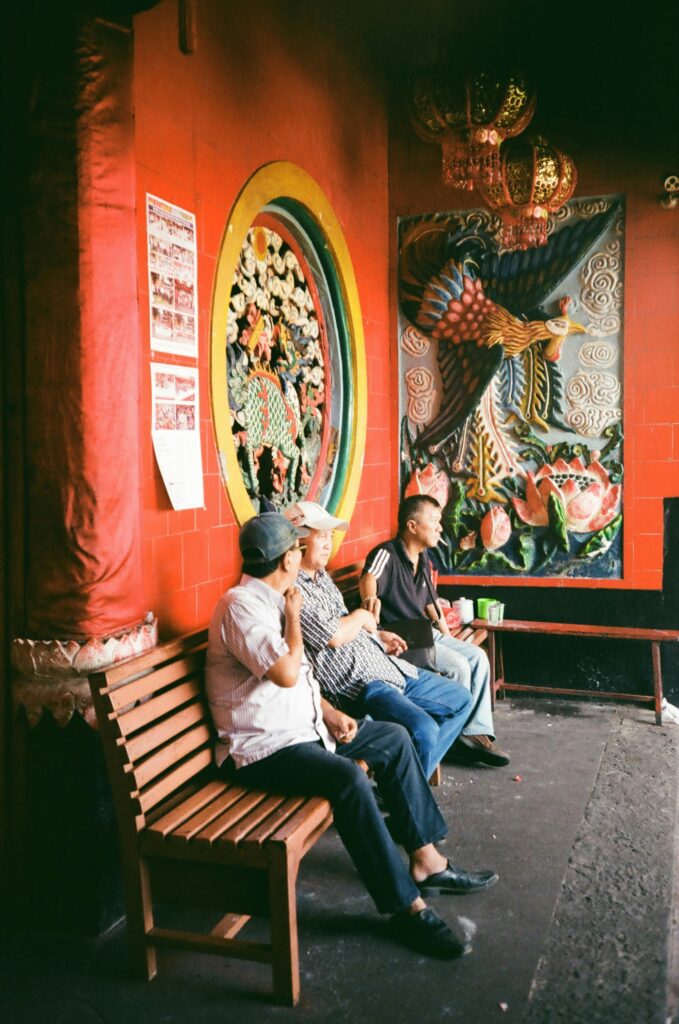

Revival of Chinese Culture

Former President Abdurrahman Wahid lifter restrictions on Chinese-language publications, leading to re-establishment of Chinese newspapers, magazines and Mandarin language schools. By 2003, former President Megawati Soekarnoputri officially recognized lunar new year as a public holiday. Also during the same year, traditional Chinese performance such as lion dance (Barongsai) became common during the public celebration.

Additionally, Chinese temples (kelenteng) and Confucianism regained official recognition, further reinforcing the revival of Chinese heritage in Indonesia. The establishment of organization involving Chinese community also provided Chinese-Indonesians with platforms for cultural promotion and political representation.

Chinese Indonesian’s Economic contribution to Modern Indonesia

Despite making only 2-3% of Indonesia’s population, the Chinese-Indonesians played a vital role in contributing to Indonesia’s economy. Many Chinese-Indonesians started as small traders and later expanding into industrial and financial giants.

Today, some of Indonesia’s most powerful conglomerates are owned by the Chinese-Indonesian. These corporations include:

- Salim Group: owners of Indofood and Indomaret, which includes the famous instant noodle, Indomie.

- Sinar Mas Group: palm oil, banking, education, and real estate.

- Astra Internationals: automobiles and plantations

- Lippo group: real-estate, healthcare, and education

- Djarum group: tobacco, banking, technology (e-commerce), and sport industry (owners of Como football club and Indonesian badminton academy).

These businesses have played crucial role in shaping Indonesia’s economic development, controlling major sectors in banking, retail, manufacturing, and real estate. Their resilience and adaptability have became key factors in their success, particularly during the 1998 Financial Crisis.

To conclude, the Chinese-Indonesians have been an integral part of Indonesia’s progress. Despite some historical setbacks, their contribution have helped shape modern Indonesia into a thriving economy and regional powerhouse.

Notable figures of Chinese Indonesian

Chinese-Indonesians have made significant contributions beyond the economic sector, excelling in various fields such as sports, technology, journalism, politics, the military, and entertainment. Here are some famous Chinese-Indonesians across different industries:

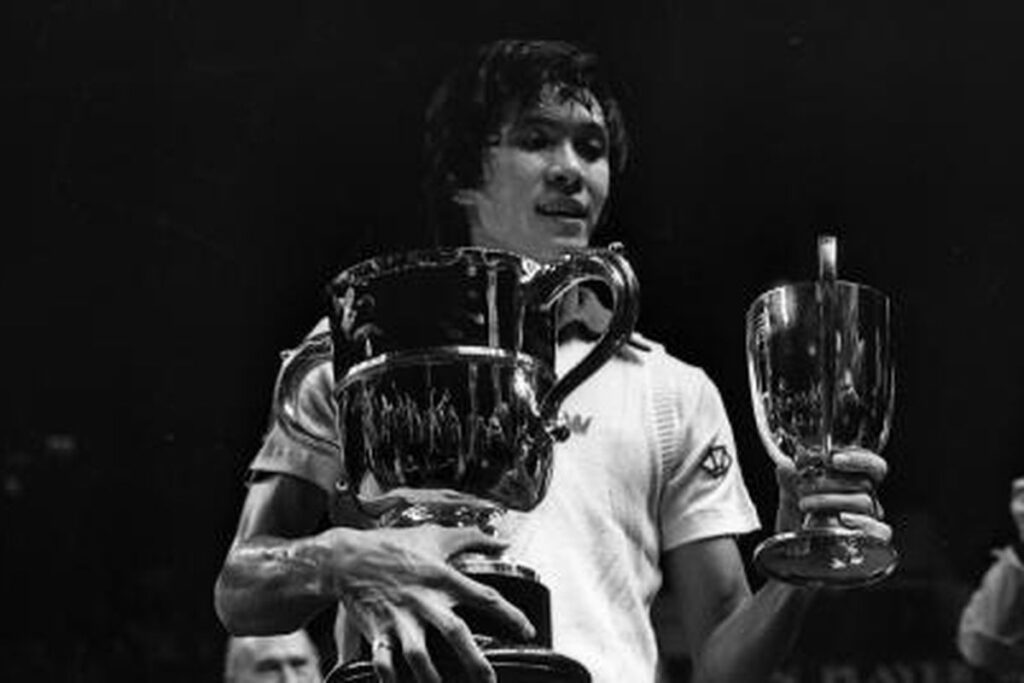

Sports

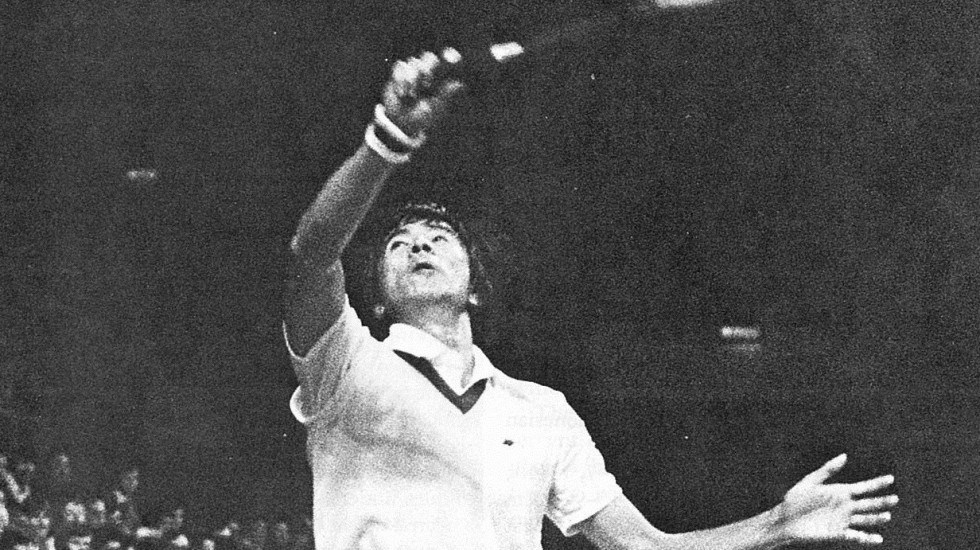

- Lim Swie King (林水鏡) – legendary badminton player, multiple-time All England champion and world cup

- Rudy Hartono (Nio Hap Liang/梁海量) – legendary badminton player, winner of world championship and multiple-time All England champion

- Susi Susanti (王蓮香) – Olympic gold medalist in badminton (1992 Barcelona)

- Alan Budikusuma (魏仁芳) – Olympic gold medalist in badminton (1992 Barcelona)

- Hendra Setiawan – Olympic gold medalist (Beijing 2008) and multiple winner of world championship

- Lilyana Natsir – Olympic gold medalist (Rio 2016) and multiple winner of world championship

- Lucas Lee – Indonesian footballer currently representing the U-17 national team, including appearances at the 2025 FIFA U-17 World Cup.

Business

- Sudono Salim (Liem Sioe Liong/林紹良) – Founder of Salim group (Indofood, Indomaret, Bogasari)

- Eka Tjipta Widjaja (Oei Ek Tjong/黃奕聰)– Founder of Sinar Mas Group (Palm oil, paper, banking, real estate)

- Robert Budi Harto (黃輝聰)– Owner of Djarum Group (Tobacco, banking, e-commerce)

- Ciputra (Tjien Tjin Hoan/徐振煥) – Property tycoon, founder of Ciputra group

- Prajogo Pangestu (Phang Djoen Phen/ 彭雲鵬) – Founder of Barito Pacific, engages in energy industry.

Politics

- Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok/钟万学) – Former governor of Jakarta, first Chinese-Christian governor in devades

- Jusuf Wanandi (林绵基)– Political analyst and co-founder of the Centre for Strategic and International studies

- Kwik Kian Gie (郭建义) – Former Coordinating Minister for the Economy

- Sherly Tjoanda – first female governor of North Maluku

- Mari Elka Pangestu (冯慧兰) – Former minister of trade and currently president’s special advisor

- Ignasius Jonan – Former Minister of Transportation and former CEO of Kereta Api Indonesia (KAI)

- Grace Natalie – co-founder and chairperson of the Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI)

Military

- John Lie (李约翰) – a national hero who served the Indonesian navy from 1947 to 1963. He retired as a rear admiral

- Teddy Jusuf ( 熊德怡) – first Chinese-Indonesian to attain the rank of Brigadier General in Indonesian army

- Iskandar Kamil (Liem Key Ho) – He led the Army’s Legal Development Agency and later became a Supreme Court judge. In August 2006, he sentenced six people to death for smuggling cocaine from Bali to Australia (Bali Nine).

Entertainers

- Agnez Mo (杨诗曼) – internationally recognized singer-songwriter and actress

- Rich Brian – internationally recognized singer-songwriter and rapper

- Joe Taslim – Hollywood and Indonesian actor, starred in The Raid, Fast & Furious 6

- Daniel Mananta – TV host, actor, and entrepreneur

- Warren Hue – Indonesian rapper, singer, and songwriter

- Ernest Prakasa – Indonesian comedian, stand up performer, writer, and actor

- Dion Wiyoko – Indonesian actor and model

Technology

- William Tanuwijaya – Co-founder and CEO of Tokopedia, one of Indonesia’s largest e-commerce platforms

- Andrew Darwis – Founder of Kaskus, Indonesia’s largest online community and forum platform

- Ferry Unardi – Co-founder & CEO of Traveloka, major online travel company

- Jerry Ng – Co-founder of Bank Jago, a digital bank transforming Indonesia’s financial sector

- Kusumo Martanto – Founder of BliBli, one of Indonesia’s biggest e-commerce marketplaces

References

https://ir.binus.ac.id/2014/01/24/tionghoa-etnik-yang-terbentuk-oleh-sejarah/

https://minorityrights.org/communities/chinese-3/

https://historia.id/politik/articles/menteri-tionghoa-di-kabinet-republik-indonesia-DEnz7/page/7

Chong, W.L. (2016) ‘Rethinking the position of ethnic Chinese Indonesians’, SEJARAH: Journal of the Department of History, 25(2), pp. 96–108. Available at: https://ejournal.um.edu.my/index.php/SEJARAH/article/view/9341

Subekti, W. (2023). Kontribusi Etnis Tionghoa pada Pergerakan Nasional Indonesia (1900-1945). Jurnal Pendidikan Sejarah & Sejarah FKIP Universitas Jambi, 2(3), pp. 12-25. doi:10.22437/krinok.v2i3.24747. Available at: https://online-journal.unja.ac.id/krinok